Well-designed and well-managed Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) can deliver high-quality and cost-efficient infrastructure, helping municipalities address critical infrastructure needs in the face of rapid urbanization and limited public funds. This Municipal PPP Framework provides municipalities with a practical guide and set of tools to enable them to identify, prepare, deliver, and manage PPP projects. Although designed to support municipal governments and staff, and so written with their perspective in mind, it is also a useful resource for decision-makers and practitioners across a range of municipal infrastructure sectors and services.

What is Municipal PPP?

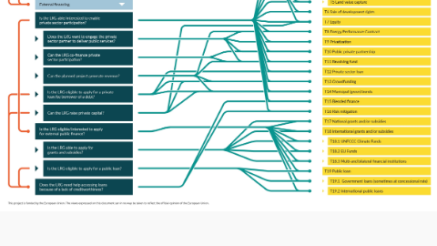

Within this Municipal PPP Framework, PPP encompasses a variety of approaches to private entities partnering with local governments to deliver infrastructure services, with the private sector making a long-term commitment and taking significant project risks. A municipal PPP is simply a PPP where the government entity is a municipal body and where the public asset or service is a municipal asset or service. It is important to note, however, that PPPs are only one of several tools available to municipalities to deliver infrastructure services in a more efficient and fiscally effective manner and the structure of a PPP used for a specific project is flexible. Each approach has different characteristics and priorities. Figure 1 shows the relationship between a few of the more common structures.

Why Municipal PPP?

The term PPP encompasses a variety of approaches to long-term partnerships between municipalities and private entities to deliver infrastructure services, with the private partner bearing significant project risks. As used herein, a municipal PPP is simply a PPP where the government entity is a municipal body and where the public asset or service is a municipal asset or service. As used throughout this framework, the term ‘municipal’ is intended to cover the many forms and names of subnational government public bodies serving local communities under different administrative, legislative, and constitutional systems around the world.

PPPs are part of a fundamental, global shift in the role of the municipal government – from being the direct provider of public services, to becoming the planner, facilitator, contract manager and/ or regulator who ensures that local services are available, reliable, meet key quality standards, and are affordable for users and the local economy. Within this broad paradigm, the structure of a PPP used for a specific project is flexible, with a wide variety of options available that allocate different rights and responsibilities to the parties to the PPP. The appropriate project structure can only be determined with reference to the unique context of the municipality and a particular project.

There are a few general principles with which the municipality should be familiar. The project structure determines the extent of the private sector’s participation in the underlying project, for instance whether the private partner is responsible only for operating and maintaining an existing asset, or whether it is responsible for designing, financing, and building a new asset. In turn, the extent of the private sector’s involvement in the project affects the amount of risk that may be transferred to the private sector. As the private partner’s role increases, so too does the amount of risk it may be asked to bear. The reverse is also true, as the private partner assumes more risk, it will require more operational control over the project in order it manage those risks.

An appropriate allocation of risks between the parties is a key determinant of project success. From the perspective of the municipality, transferring risk to the private partner is a significant benefit of a PPP, for instance the risk that construction is completed on time and according to specifications. At the same time, the private partner will need to be compensated for risk borne. Thus, the more risk that is transferred to the private partner, the higher the cost of capital. As a PPP is never “free” from the perspective of the municipality, the cost of capital is a major factor in evaluating whether a PPP is the most desirable delivery method for a particular project. Transferring too much risk to the private partner can unduly increase the cost of the project and even result in project failure.

A PPP requires careful preparation. This begins at the earliest stage of project identification and continues through final execution of the PPP agreement, as more project-specific details and data become known. If well-designed and managed, PPPs can deliver high-quality, cost-efficient infrastructure, while leveraging private capital to increase the amount of infrastructure that can be delivered by the municipality within the same budgetary envelope. PPPs can help municipalities deliver better and more reliable quality of service at a better cost to the municipality when compared to what can be achieved by public sector delivery alone. By mobilizing private expertise, human, and financial resources, PPPs can accelerate the construction of infrastructure, improve the efficiency of public services, and foster innovative solutions that offer a better response to user needs than would often poorly functioning public service provision.

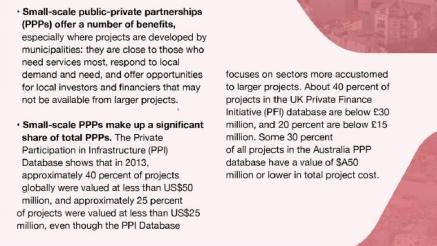

At the same time, PPPs are only one of many tools available to municipalities to meet their infrastructure needs and should be viewed as such. The private sector can do some things better than the public sector, in particular around innovation, service delivery, commercial orientation, and operational efficiency. When properly structured, a PPP can leverage the distinct incentives and capabilities of the private sector and create “win-win” arrangements. However, a PPP will not always be the most effective option for delivering a particular project and implementing a PPP presents unique challenges for the municipality, including increased project preparation requirements, direct and contingent fiscal liabilities, and oversight responsibilities.

In considering whether and why to pursue a PPP, the municipality needs to consider the relative pros and cons of using PPP as compared to the other options for delivering the same project, in particular through the lens of efficient service delivery, public investment management, fiscal risk management, and capital planning; i.e. whether the project represents “value for money” or “VfM”. To this end, the municipality should assess how PPPs factor into its broader planning and budgeting systems, and ensure adequate processes are in place to determine the most effective use of limited public resources and fiscal space.

Understanding the Context

Before attempting a particular PPP project or program, the municipality must understand the broader context in which the project will be developed and delivered. This includes the public sector context, from institutional capacity to funding PPP, and the private sector context, namely the key issues and concerns that will influence private investors’ interest in investing in a PPP project.

PUBLIC

Before considering the potential to implement a PPP, it is important to first clearly understand the municipality’s context as it relates to successful PPP delivery. Key issues include:

- The municipality’s investment planning and budgeting processes;

- The institutional capacity of the municipality to deliver a PPP, including its internal human resources and its ability to procure outside advisers to assist with project preparatory work;

- The municipality’s creditworthiness, financial capacity, and overall credibility as a contractual partner; and

- The applicable legal and regulatory framework, including as it relates to the municipality’s legal authority to enter into a binding PPP agreement.

FUNDING PPP

Municipal PPPs need a robust revenue stream to fund capital and operating expenses, including debt service and equity return. The municipality should follow a hierarchy of possible revenue sources that begins with maximizing sustainable revenues from direct beneficiaries, then explores options to capture value from indirect beneficiaries. Finally, and only then, should public money or guarantees be used to enhance project viability, and only where that public support represents VfM for the government, the community, and the economy.

PRIVATE

In preparing and structuring a municipal PPP, the municipality should consider the project from the perspective of a private partner. In particular, a private investor will want to know that the project is well-studied and -prepared, with reliable forecasts of costs, demand, and revenue, as well as an appropriate allocation of risks. A prospective private partner will also be concerned with the broader context in which the project will operate. It will need confidence that the municipality will fulfill its contractual obligations and will have the capacity and intention to make any payments due under the PPP. If foreign investment is sought, private investors and lenders will need a means to manage foreign exchange risk and will need to trust the domestic courts to fairly adjudicate contractual claims or enforce arbitration awards, should a dispute arise. By considering issues like these from the outset, the municipality will increase the likelihood of identifying, preparing, and procuring a successful PPP.

PPP Project Cycle

The full life-cycle of a PPP consists of four phases: i) selection; ii) development; iii) procurement and award; and iv) implementation. These phases are not necessarily linear, a project may move back and forth between these phases as needed to ensure that it is well prepared. Furthermore, in some jurisdictions the applicable legal and regulatory framework may set out specific requirements and processes that must be followed with respect to some or all the stages in the project cycle. Implementing a successful PPP requires significant upfront investment, both in terms of time and money, but this investment will generate substantial benefits over the life of the project and greatly reduce the likelihood of costly changes or otherwise incurring significant liabilities from the project in the future. A robust development process will help ensure, among other things, that the project:

- Provides value for money to the municipality versus other delivery options;

- Does not expose the municipality to excessive liabilities;

- Attracts more and higher quality bidders, which increases competition and so may reduce the project cost, and makes it more likely that the winning bidder will have the capacity to deliver the project to the municipality’s specifications;

- Minimizes or eliminates negative environmental or social impacts from the project; and

- Provides high quality and affordable services to the project’s beneficiaries.

Failure to invest adequate time and resources for project development can reduce the value of the project, result in significant costs for the municipality, and make the project more likely to fail. The municipality is unlikely to have sufficient internal human resources in this regard, especially when undertaking its first PPP project or program. Internal human resource capacity can and should be developed over time, through appropriate hiring, formal trainings, and direct, on-the-job experience with PPPs. In many respects, expertise is best acquired by actually working on a PPP (i.e., learn-by-doing), provided that emphasis is placed on knowledge sharing to ensure that lessons learned are shared among staff and preserved within institutions despite staffing changes.

In the interim, gaps in internal capacity can be overcome by seeking external assistance with project development. To this end, recourse may be made to national or state-level PPP units and other government departments and entities at the local or national level with PPP experience that can provide hands-on support to the municipality. In addition, the municipality will almost certainly need to procure qualified, third-party consultants for project-level advisory services. This may include assistance with initial project selection, preparation of a feasibility study, and transaction advice through to selection of the private partner, signing the PPP agreement, and financial close. Costs for these services vary significantly based on the size and complexity of the project and the capacity of the municipality. These services may be paid for by national or local PPP units or by the municipality directly from various funding sources (e.g., technical assistance from development partners, or special funds created for such purpose at the national or state-level, among others).