May 19, 2020

By

Fighting Infectious Diseases: the Connection to Climate Change

Photo by Maksym Kaharlytskyi on Unsplash

As global temperatures rise, long-term changes in climate and wildlife habitat could have a significant effect on human health and increase the risk of infectious diseases like the coronavirus (COVID-19). Here are four reasons the battle against infectious diseases and pandemics is also about the fight against climate change.

Climate variability and climate change are affecting infectious-disease transmission patterns in multiple ways. For example, diseases traditionally associated with tropical and subtropical regions are reaching new areas of the world. Rising temperatures and precipitation are making temperate, northern or mountainous countries more susceptible to outbreaks of "southern" or “low land” diseases like malaria. Nepal, previously too cool for dengue fever, suffered its first outbreak in 2006, with a handful of cases. Since then, the incidence of dengue has increased significantly. Before 1970, dengue fever caused severe outbreaks in only nine countries. Now it is endemic in more than 100 countries, according to the World Health Organization.

A projected increase in the frequency and intensity of disasters associated with climate change could displace a growing number of people. The World Bank estimates that, in three regions alone, there will be 140 million internally displaced people by 2050 due to climate change. As people migrate, they not only place substantial demands on the ecosystems and social infrastructures where they move, but also carry illnesses that emerge from shifts in infectious-disease vectors.

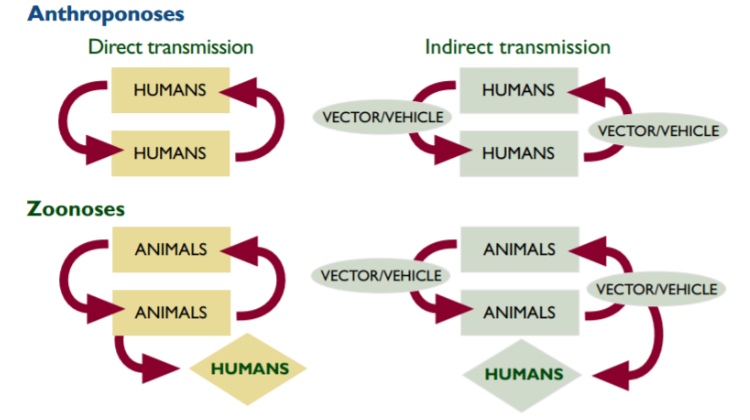

And a loss of wildlife habitat is linked both to climate change and to disease outbreaks. An estimated 75% of new infectious diseases are zoonotic, meaning they transmit from animals to humans. Experts believe these diseases may be associated with increased human-to-animal contact as people encroach on animal habitats. Deforestation and mass forest fires are also responsible for habitat loss: they contribute to climate change or are caused by it, creating a feedback loop. According to EcoHealthAlliance, deforestation is linked to 31% of disease outbreaks such as the Ebola, Zika and Nipah viruses.

Figure 1 provides a framework on infectious disease transmission types, including human to human, animal to animal, and animal to human. Climate change is increasing the global emergence, resurgence and redistribution of infectious diseases risks across all of these.

Figure 1 - Four main types of transmission cycle for infectious diseases. Source: WHO https://www.who.int/globalchange/summary/en/index5.html

Fine particulate pollution such as black carbon, sulfates and nitrates penetrate deep into the bloodstream and lungs, creating serious health impacts; these are also known to weaken the immune system. Preliminary research by Greenpeace in Italy, Harvard University in the United States, and Martin Luther University Halle-Wittenberg in Germany suggests that air pollution increases the risk of COVID-19 spreading faster and becoming deadlier. New York City, Lombardy in Italy, and China’s Wuhan province – all urban, industrial areas with high levels of air pollution – were heavily impacted by the coronavirus. Scientists have suggested that air pollution particles may also act as vehicles for viral transmission. An increase in fine particulate pollution of just 1 microgram per cubic meter corresponded to a 15% increase in COVID-19 deaths. Sources of air pollution in cities – traffic, waste, energy and industry – are also the main sources of greenhouse gas emissions. Improving air quality and reducing emissions, especially in cities, could have significant benefits for fighting both viral and climate risks.

Temperatures in the Arctic Circle are rising quickly -- about three times faster than in the rest of the world. As ice and permafrost melt, it not only further accelerates climate change, but infectious agents may (re)emerge. Permafrost is a very good preserver of microbes and viruses because it is cold, devoid of oxygen, and dark. Scientific studies show that certain pathogens such as bacteria, viruses and fungi can survive even after being frozen for hundreds, thousands, even millions of years. For instance, scientists have discovered fragments of ribonucleic acid (RNA) from the 1918 Spanish flu virus in corpses buried in mass graves in Alaska's tundra. In 2016, a 12-year-old child died and 20 people were infected by anthrax in a remote part of Siberia where a heat wave had thawed permafrost soil, exposing the corpse of a reindeer that had died 75 years earlier from the disease. Another team of researchers collected samples of the earth’s oldest glacial ice from 50 meters below the surface in Tibet and uncovered 28 ancient viruses previously unknown to scientists. As ice melts due to climate change, there are concerns that pathogens could be released for which our immune systems would be unprepared.

A changing climate could also unlock new infectious diseases as pathogens mutate and evolve to adapt to warmer temperatures in much of the world. A study published by Johns Hopkins University in January 2020 raises concern that climate change will cause new heat-tolerant diseases to evolve that jeopardize one of our key natural defenses – fever, the ability of mammals to maintain high temperatures to fight infections.

"Fighting global health risks and diseases, including outbreaks with pandemic potential, is also, fundamentally, about fighting climate change. We need to treat the health of humans, animals, the economy and the planet as one."

Addressing climate and infectious diseases simultaneously

Scientific evidence points to the need for accurate forecasting and monitoring of climate change and its impact on infectious diseases. This effort must be coupled with enhanced surveillance systems and technologies for detecting human and animal diseases to provide early information about new pathogenic microbes. More cross-country cooperation will be needed to identify and mount a public health response to outbreaks and epidemics.

Scientific evidence points to the need for accurate forecasting and monitoring of climate change and its impact on infectious diseases. This effort must be coupled with enhanced surveillance systems and technologies for detecting human and animal diseases to provide early information about new pathogenic microbes. More cross-country cooperation will be needed to identify and mount a public health response to outbreaks and epidemics.

Like infectious diseases, greenhouse gas emissions know no borders. Global cooperation is needed to address both. Combating climate change as a root cause of disease transmission can also simultaneously mitigate the threats of biodiversity loss and pandemics. The world will have an opportunity in the pandemic recovery to strengthen the link between the health and climate agendas. Countries can prioritize investments that help meet their overall climate commitments, while addressing climate and environmental impacts on health. Fighting global health risks and diseases, including outbreaks with pandemic potential, is also, fundamentally, about fighting climate change. We need to treat the health of humans, animals, the economy and the planet as one.

Originally published on here